Results

Clients

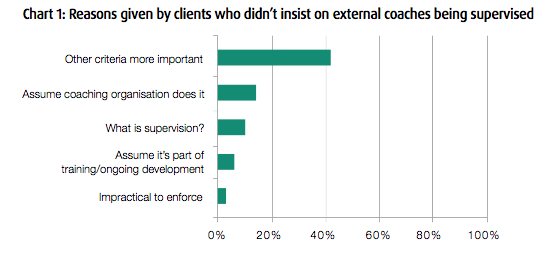

79% of clients said they didn’t insist on coaches being supervised (chart 1). 41% believe other factors are more important (e.g. coaching qualifications, coaching experience). 14% assume that the relevant coaching organisation supervise their coaches on the clients’ behalf. 10% of respondents said they didn’t know what coaching supervision was.

Coaches

Satisfying different purposes

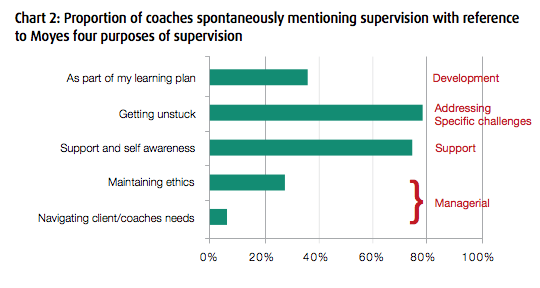

Although supervision was mentioned most often, most coaches used it in this context as a last resort, only if other activities didn’t yield a satisfactory solution. With reference to Moyes’ (2009) four purposes, almost 80% of coaches said they considered supervision if they got stuck in an assignment or if they needed support (chart 2). 36% mentioned supervision as a component of their ongoing learning plan, 27% said they used supervision to ensure they were practicing ethically and just 6% mentioned supervision as part of their strategy for ensuring they successfully navigated the needs of both client and coachee. These last two factors are both aspects of Moyes fourth purpose – ‘managerial’.

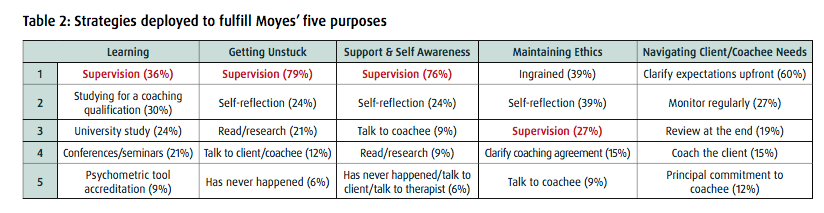

Supervision was mentioned less often with respect to monitoring adherence to coaching ethics. 39% of coaches talked about their sense of ethics being ingrained. These coaches had an average of 8.75 years of coaching experience, not markedly different to the overall average of 8.2 years, reflecting the fact that some coaches come into coaching with an existing ethical code formed while working in another profession (e.g. legal, social work). When asked which coaching ethics they subscribed to, 54% referred to ICF ethics and 30% to Getting unstuck professional psychology ethics.

Supervision was mentioned less often with respect to monitoring adherence to coaching ethics. 39% of coaches talked about their sense of ethics being ingrained. These coaches had an average of 8.75 years of coaching experience, not markedly different to the overall average of 8.2 years, reflecting the fact that some coaches come into coaching with an existing ethical code formed while working in another profession (e.g. legal, social work). When asked which coaching ethics they subscribed to, 54% referred to ICF ethics and 30% to Getting unstuck professional psychology ethics.

Specific challenges Support Managerial

Only 6% of coaches talked about using supervision to navigate the potentially conflicting needs of client and coachee, despite the challenges this can present. 85% of respondents said their primary strategy was to establish expectations up front with all parties, often seeking a 3-way meeting between coach, coachee, and client.

Coaches reported other activities that served to fulfill each of these needs (table 2):

Relatively few coaches checked back in with the client during the assignment (27%) or at the end of an assignment (15%). Several coaches talked about some of the challenges they encountered in seeking to engage a third party, how ‘tricky’ it could be to manage the ‘coaching triangle’ of coach, coachee and client, how it felt like a ‘balancing act’, and of the need to stay vigilant throughout the assignment. One participant avoided the coaching triangle entirely. Others spoke of doing their best to manage the coaching triangle, but siding with the coachee if necessary.

Relatively few coaches checked back in with the client during the assignment (27%) or at the end of an assignment (15%). Several coaches talked about some of the challenges they encountered in seeking to engage a third party, how ‘tricky’ it could be to manage the ‘coaching triangle’ of coach, coachee and client, how it felt like a ‘balancing act’, and of the need to stay vigilant throughout the assignment. One participant avoided the coaching triangle entirely. Others spoke of doing their best to manage the coaching triangle, but siding with the coachee if necessary.

Why undertake supervision?

After we asked coaches how they managed Moyes’ (2009) four different purposes of supervision, we asked them directly why they undertook supervision, and what impact it had had on their practice. Coaches responding to this question placed most emphasis on self development and/or self awareness. As suggested before, though many coaches may turn to supervision to address specific issues and to seek support, many report rarely experiencing the need for support in these areas. The primary purpose for many coaches seems to be developmental. This hypothesis appears to be supported by answers to the question ‘How has supervision changed your practice?’ 58% talked about their development generally, and most of the other changes mentioned relate to specific aspects of development, including confidence and self awareness, and the capacities to reflect and be present.

Different forms of supervision

We categorised the practices we heard described with reference to four parameters:

» Formal or informal: whether or not the relationship had been established explicitly as a supervisor-supervisee, or peer supervision process.

» Individual or group: one-to-one, or as part of a group.

» Regular or ad-hoc: whether or not sessions were held on a regular basis. Several participants sought out the services of a supervisor when required, often with reference to a specific issue, or according to the volume of coaching work they were undertaking at any one time.

» Paid or unpaid: whether or not the coach paid the individual or group supervisor.

These four parameters give us 16 possible forms of supervision.

The most popular form of ‘supervision’ was informal 1-to-1 consultation with colleagues on an ad-hoc basis. Some coaches called this supervision, others didn’t. Five of the coaches we spoke to undertook only informal supervision. When asked why they didn’t undertake formal supervision, answers included:

“I could pay, but I don’t have many clients at the moment, and I don’t know if other coaches do. If you say you don’t have many clients, there’s a fear of being seen as a failure.”

“I think it’s a good idea for new coaches. I don’t feel the need for it after x years. Who would I get to supervise me? Who has more experience than me? I make up my own rules thanks! My clients don’t care so why should I?”

“I undertake supervision when I need it, usually when I get stuck, which hasn’t happened for a while. I often talk with my business partners about things; particular approaches, sharing learnings, the process of coaching.”

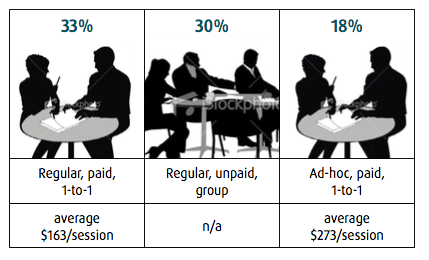

Of the other forms of supervision three were particularly popular, all of them formal:

Regular, paid, 1-to-1 supervision isn’t necessarily ‘professional supervision’ as defined in the Standards Australia Guidelines, since few coaches sought out someone specifically trained to be a coach supervisor. Many sought out the services of a registered psychologist, but not specifically one with supervision training. Unpaid group supervision was a popular form of supervision amongst the New Zealand coaches we spoke to, and psychologists generally. These coaches found peer supervisors through psychology networks, ICF networks, or both. Some groups included HR professionals and consultants. Coaches seeking paid 1-to-1 supervision on an ad-hoc basis tended to be more experienced than the group as a whole (9.8 years vs. 8.2 years) and paid significantly more for the supervision they received than those undergoing regular individual supervision.

Regular, paid, 1-to-1 supervision isn’t necessarily ‘professional supervision’ as defined in the Standards Australia Guidelines, since few coaches sought out someone specifically trained to be a coach supervisor. Many sought out the services of a registered psychologist, but not specifically one with supervision training. Unpaid group supervision was a popular form of supervision amongst the New Zealand coaches we spoke to, and psychologists generally. These coaches found peer supervisors through psychology networks, ICF networks, or both. Some groups included HR professionals and consultants. Coaches seeking paid 1-to-1 supervision on an ad-hoc basis tended to be more experienced than the group as a whole (9.8 years vs. 8.2 years) and paid significantly more for the supervision they received than those undergoing regular individual supervision.

Discussion

85% of the coaches we spoke to undertook some form of formal supervision, and 33% undertook formal, regular, paid, one-to-one supervision. These numbers are consistent with those reported by Grant (2011) and Passmore & McGoldrick (2009).

We found no evidence to support Passmore & McGoldricks’ suggestion that sole practitioners may be less likely to undergo supervision than coaches working within organisations. Most of the sole practitioners we spoke to appeared to value working with other practitioners in the field, and were just as likely to pay for formal regular supervision on a one-to-one basis.

Consistent with Passmore & McGoldricks’ suggestion that new coaches may benefit most from group supervision, we did find that coaches undertaking individual supervision tended to be more experienced than those undergoing group supervision (8.9 years experience vs. 6.3 years). This may reflect the specific needs of some of the more experienced coaches we spoke to, which they felt they could satisfy best by looking for specialists, often based outside Australia.

We didn’t find evidence that coaches seek supervision from therapists because they are more available and cheaper (Farmer, 2012). Those coaches seeking paid 1-to-1 supervision appeared to have clear criteria as to who they wanted to work with, often seeking the services of a registered psychologist. The cost- conscious seem more likely to choose peer supervision rather than relatively cheap 1-to-1 supervision.

With reference to Gray (2010) and Grant (2011), who both discussed the value of a networked approach to supervision, we found plentiful evidence that many coaches do seek the services of supervisors with specific qualities to fulfill a specific purpose. Moreover we found that some coaches may seek out those services at the time they need them, such that effective supervision may not always be regular.

Different approaches to coaching supervision

We identified three approaches to coaching supervision:

⦁ Supervisor as coach

Most definitions of supervision focus on the importance of reflective practice in the service of ongoing learning, be it in coaching or supervision. Thomson (2011), for example, cites Christian & Kitto (1987) in defining supervision simply as “a process whereby one person enables another to think better.” Accordingly, the ICF definition of supervision implies

that supervision is a similar process to coaching, such that an experienced coach can effectively play the role of supervisor.

⦁ Supervisor as systems thinker

The Standards Australia guidelines, on the other hand, state that supervision “… is not simply coaching the coach,” and it requires “particular knowledge of the dynamics of helping relationships within the helper.” Hawkins & Smith (2006) are more explicit in suggesting that a coaching supervisor should be able to adopt a systemic approach. For them supervision is a process by which the supervisor helps the coach to “attend to better understanding both the client system and themselves … and transform their work.”

⦁ Supervisor as professionally accredited expert

The Standards Australia Guidelines for Coaching in Organizations says that “All coaches should be engaged in professional supervision.” Cavanagh and Lane (2012) suggest that markers of traditional professions include “…practice licensed only to qualified members (and achieved through hours served and accreditation) …” implying that supervisors should be formally recognised as being more ‘expert’. Gray (2010) suggests that “supervision often involves an element of assessment and critical judgement,” and that “evaluation is the final function of the supervision process.” Armstrong & Geddes (2009) disagree. They say “… supervision in other contexts … has a monitoring function but, within an as yet unregulated field, there is little place for this except in certain situations, for example, for an accredited training provider and employer of coaches …”

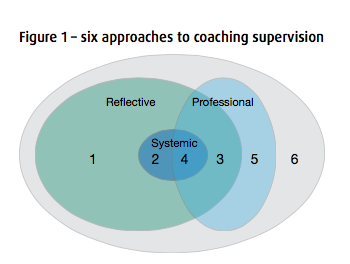

These approaches are not mutually exclusive (figure 1), such that we can identify six approaches to coaching & coaching supervision. The coach’s attitude to supervision is likely to depend on which category of coach they best fit.

⦁ Reflective practice

Many coaches value reflective practice, engaging the services of a supervisor to help them learn and develop, and/or to reflect on difficult assignments. They may equally value individual or group coaching, so long as there is an emphasis on reflective practice.

⦁ Reflective/systemic practice

These coaches adopt a systemic perspective. Their supervision requirements are similar to those of reflective coaches, although they will expect their supervisor or group to help them gain further insights into how they can operate more effectively within the organisational system. When such support is hard to find, the reflective systemic coach may be more likely to seek a personal supervisor.

⦁ Reflective/professional practice

These coaches belong to a professional body with clearly defined competencies, enforced entry criteria, and specific supervision requirements (e.g. the APS and NZPS). These coaches value reflective practice, and are more likely to adopt a level-of-competency lens through which they regard other coaches. They may equally value individual or group coaching, depending on the requirements of their professional body.

⦁ Reflective/systemic/professional practice

These coaches value reflective practice, adopt a systemic perspective, and belong to a professional body with specific supervision requirements. Like reflective/systemic coaches, when systemic supervisors are hard to find, these coaches may undertake 1-to-1 supervision regardless of the requirements of their professional body.

⦁ Non-reflective professional practice

These coaches don’t appear to value reflective practice. Their philosophy of coaching may be more didactic or transactional. They may nevertheless engage in supervision, but their primary purpose for attending supervision is to satisfy the requirements of their professional body.

⦁ Non-reflective practice

These coaches don’t particularly value reflective practice, nor do they feel obliged to attend supervision. Instead they may seek guidance or instruction from subject-matter-experts relevant to their mode of coaching. Their coaching approach is likely to be more didactic, an approach which some people might label as ‘mentoring’ or ‘consulting’ depending on their own world-view.

Barriers to supervision

Passmore & McGoldrick (2009) suggest the main barrier to coaching supervision is that coaches are told to undertake supervision without knowing why. The results of our study support the idea that many coaches don’t understand why they should be expected to undertake ‘formal’ supervision, if that implies paid, regular, 1-to-1 supervision with a qualified supervisor.

Many coaches seem to be satisfied with other means by which to satisfy their various needs as defined by Moyes (2009).

Our study doesn’t support the idea that cost is a principal barrier to supervision (Grant, 2011). Many of the coaches we spoke to find their needs met by unpaid forms of supervision, in particular unpaid group supervision. Many coaches don’t aspire

to undertake ‘formal’ supervision.

Our findings support the idea that the notion that all coaches should undertake paid,

regular, 1-to-1 supervision with a qualified supervisor may have been imported

from the world of clinical psychology/ psychotherapy & counselling, and has yet to be properly challenged as to its relevance for executive coaching. Not all coaches

seek 1-to-1 supervision, nor do they all seek regular supervision. The drive for this form of supervision may emanate from professional bodies seeking assurance that their members are undergoing minimum levels of reflective practice in the company of ‘experts’.

Some coaches, in particular more experienced coaches, did report difficulties in finding a supervisor with the attributes they were looking for, such that several were working with supervisors based overseas, communicating by telephone. Few though mentioned supervisory qualifications per se as the attribute they were looking for. Often it was someone with more coaching experience, or more experience in a particular discipline.

Conclusions

In conclusion then, we don’t find ourselves in agreement with the Standards Australia Guidelines for Coaching in Organizations when it says: “All coaches should be engaged in professional supervision.” We see this as a valid perspective, but not the only perspective. On the other hand we do agree with the Standards when they say:

Coaches should be able to articulate to their clients the nature and extent of their training and the evidence underpinning their practice. Similarly, coaches should include regular reflective processes to assist in the formulation of their ongoing professional development …

We hope that our five questions, derived from the work of Moyes (2009) and others, will provide a pragmatic and easy-to-use methodology to get to the heart of the matter.

____________________

References

Armstrong, H. & Geddes, M. (2009). Developing Coaching Supervision Practice: an Australian case study. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 1-17

Butwell, J. (2006). Group supervision for coaches: is it worthwhile? A study of the process in a major professional organisation. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring Vol. 4, No.2, pp. 43-53

Campone, F. (2011 The reflective coaching practitioner model. In Passmore, J. (ed.). Supervision in Coaching: Supervision. Ethics and Continuous Professional Development. London: Kogan Page.

Carroll, M. (2009). Supervision: Critical Reflection for Transformational Learning (Part 1). The Clinical Supervisor, Vol. 28, pp. 210-220

Carroll, M. (2010). Supervision: Critical Reflection for Transformational Learning (Part 2). The Clinical Supervisor, Vol. 29, pp. 1-19

Cavanagh, M. & Lane, D. (2012). Coaching Psychology Coming of Age: The challenges we face in the messy world of complexity. International Coaching Psychology Review. Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 75-90

Childs, R., Woods, M., Willcock, D. & Man, A. (2011). Action learning supervision for coaches. In Passmore, J. (ed.). Supervision in Coaching: Supervision. Ethics and Continuous Professional Development. London: Kogan Page.

De Haan, E. (2008) Becoming simultaneously thicker and thinner skinned. The inherent conflicts arising in the professional development of coaches. Personnel Review Vol. 37, No. 5 pp. 526-542

Farmer, S. (2012). How does a coach know that they have found the right supervisor? Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice. Vol. 5, No. 1,

pp. 37-42

Grant, A.M. (2012). Australian Coaches’ Views on Coaching Supervision: A Study with Implications for Australian Coach Education, Training and Practice. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 17-33

Gray, D.E. (2007). Towards a systemic model of coaching supervision: Some lessons from psychotherapeutic and counselling models. Australian Psychologist, Vol. 42, No. 4, pp. 300-309

Gray, D.E. (2012). Towards the lifelong skills and business development of coaches: an integrated model of supervision and mentoring. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice. Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 60-72

Hain, D., Hain, P. & Matthewman, L. (2011). Continuous professional development for coaches. In Passmore, J. (ed.). Carroll, M. (2006). Key issues in coaching psychology supervision. The Coaching Psychologist, Vol. 2, No. 1 pp. 4-8

Hawkins, P. & Smith, N. (2006). Coaching, Mentoring and Organizational Consultancy. Open University Press. UK, US ICF position regarding coaching supervision. www. coachfederation.org/icfcedentials/supervision

Kemp, T. (2008). Self-management and the coaching relationship: Exploring coaching impact beyond models and methods. International Coaching Psychology Review. Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 32-42

Moyes, B. (2009). Literature review of coaching supervision. International Coaching Psychology Review. Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 162-173

Moyes, B. (2011). Self-supervision using a peer group model. In Passmore, J. (ed.). Supervision in Coaching: Supervision. Ethics and Continuous Professional Development. London: Kogan Page.

Passmore, J. & McGoldrick, S. (2009). Super-vision, extra-vision or blind faith? A grounded theory study of the efficacy of coaching supervision. International Coaching Psychology Review. Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 145-161

Passmore, J. (2011). Supervision and continuous professional development in coaching. In J. Passmore (ed.). Supervision in Coaching: Understanding coaching supervision, ethics, CPD and the law. London: Kogan Page.

Patel, Z. (2012): Supervision in coaching: supervision, ethics and continuous professional development, Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice. Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 62-64

Standards Australia Guidelines for Coaching in Organizations, Standards Australia, 2010

Thomson, M. (2011). Non-directive supervision of coaching. In Passmore, J. (ed.). Supervision in Coaching: Supervision. Ethics and Continuous Professional Development. London: Kogan Page.