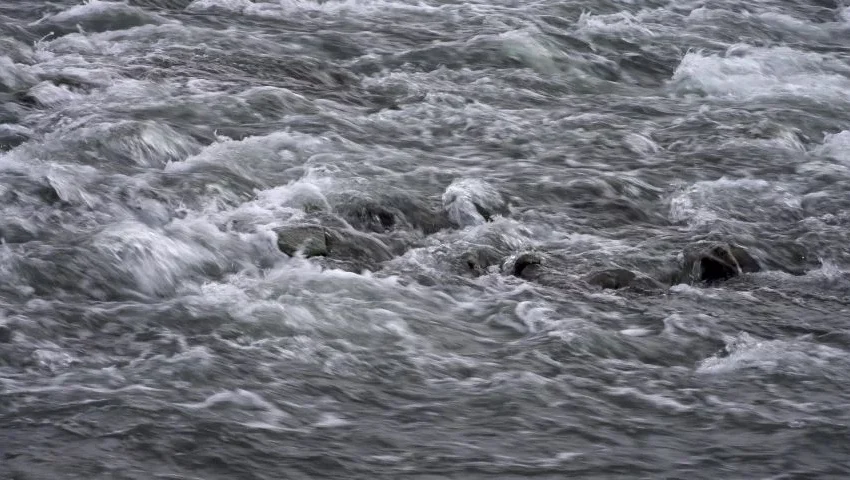

Third, I launch my kayak on the turbulent river knowing that I will make mistakes. I will have to frequently correct myself (one of the reasons to embark on the journey in a kayak rather than less “agile” canoe or skiff). Vaill (1996, p. 82) submits that a successful reflective learner “is able to see the learning process as continual experimentation rather than a system that gives the learner only one or two chances to ‘get it right.’” As Argyris and Schön (1978) often emphasized, one is successful in facing challenging times not by avoiding mistakes, but instead by learning from these mistakes and avoiding the same mistakes a second or third time. Ongoing organizational learning is based on this tolerance of mistakes but intolerance of repeated mistakes. The term “action research” is often used to describe the tight feedback-based process identified by Argyris and Schön.

Vaill (1996, pp. 70-71) actually moves beyond the notion of action research when borrowing from the concept of “action learning” that has been used by R. W. Revans (1986):

“A pioneer in this point of view is Revans, with his process of action learning (Revans, 1986}. In the United States, action learning means taking action in an organization, learning from the results, and incorporating that learning into further action. (This process is also often called action research.) Revans’s idea of action learning is quite different: it is to create learning teams of working managers to work on real organizational problems and to structure the experience in such a wav that both useful solutions to these problems emerge and substantial learning occurs for participants, learning that goes beyond the technical details of the particular problem. Interpersonal relationship learning occurs through group meetings as participants learn from each other and from those they must consult, historical learning occurs from seeing the problem through time, strategic learning occurs through seeing the problem in relation to broader organizational objectives and processes, and paradigmatic learning occurs through challenging underlying assumptions. In the process, traditional ways of doing things move from being sacred to being problematic; and in general, the whole matrix of policies and practices and ideas within which the problem resides become the objectives of group interaction and mutual learning. As Revans neatly sums up the concepts, “real people learn with and from other real people by working together in real time on real problems” (p. 75).”

With the process of action research –and action learning in particular—in place, we are moving from assimilation to accommodation when adjusting to the mistakes that have been made

Accommodation: We must be open to doing things differently when we have made a mistake. As Peter Vaill (1996, p. 82) notes, this means that we must be conscious of the fact that we are about to learn something new and are about to try out something different. In a learning organization, an assumption is made that everyone will be engaged in ongoing growth through learning. Vaill (1996, p. 82) suggests that this means we should feel free “to ask for help without embarrassment of apology and [are] able to be non-resentfully dependent on someone who has more knowledge or expertise.” The assumption of ongoing learning and growth is accompanied by a commitment to psychological safety (Edmondson, 2018)—alongside training, mentoring, appropriate levels of authority and accountability, and commitment to measurement.

Download Article