Beyond the ingredients and skills needed for a team to become collectively intelligent and for an organization to be saturated with learning is the creation of a supportive environment. Members or a team and organization must forgo their competitive spirit (at least with one another). A culture of individualism and individual gain must be discouraged. On the positive side is the critical role played by a culture of collaboration. Members of the team and organization must be willing (even eager) to work with one another. They must find gratification in the relationships established with other team members and enjoy the collegiality that comes with “winning” as a team rather than as an individual. Most importantly, members of the team and organization must appreciate the strengths shown by one another as well as the moments when they are effective at communicating, managing conflict, solving problems and making decisions. These are the key strengths to be found in what I have titled the Empowerment Pyramid (Bergquist, 2003).

Leader as Learner: At the heart of the matter regarding collective learning and collective learning is the example set by the leader as a learner. Peter Vaill uses the awkward term “leaderly learning” (Vaill, 1996, p. 127) when labeling the leader’s ongoing process of learning. I would add to what Vaill has offered by suggesting that there is an accompanying multi-tiered impact of the leader’s ongoing learning on the system they are leading. Beyond just being an exemplar, the leader will find ways to improve their own functioning through learning from the feedback offered by those with whom they work. Their own insights gained from learning something new will also contribute to the overall collective learning and intelligence of their system.

To push even further, I would suggest that leaderly learning requires what Otto Scharmer (2019) had identified as “learning into the future.” Scharmer offers a “Theory U” way of thinking about and acting in a world of turbulence. He writes about anticipatory learning. In order to engage in this learning, Scharmer suggests that we must first seek to change the system as it now exists. Scharmer is emulating John Dewey’s suggestion that we only understand something when we give it a kick and observe it’s reaction. However, Scharmer goes further than Dewey. He suggests that we must examine and often transform our own way of thinking in the world—which requires both balance and agility—if this change is to be effective and if we are to learn from this change in preparation for the future.

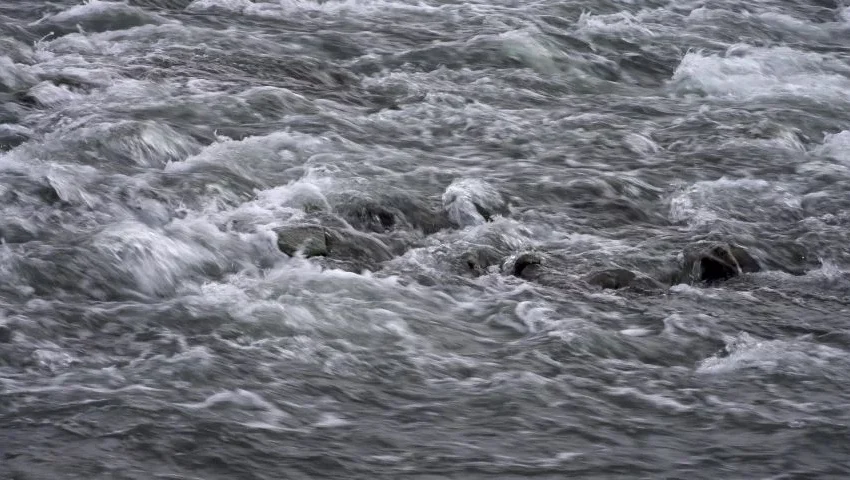

From the perspective of whitewater navigation, this would mean that we experiment with different ways of engaging our kayak in our current whitewater world. We particularly try out some changes that might make sense in terms of how the river is likely to operate around the next bend. Will there be more rocks, greater drop in elevation, more bends, etc. We take “notes” on how our kayak is behaving in response to changes in our use of the paddle, our way of sitting in the kayak, etc.

Scharmer requires that we not only try out several ways of kayaking, and take notes on these trials, but also explore and embrace new ways of thinking about the kayak and the dynamic way it operates in the river’s turbulence. These new ways are activated by what we have learned from the current trials. The new ways, in turn, influence other changes we might wish to try out before reaching the next bend in the river. Effective learning, in other words, becomes recursive and directed toward (leaning toward) the future.

Download Article